When writing Go code, you have a lot of freedom in how you organize things, but there are some common pitfalls to avoid. One of them is what I’m calling the crab pattern. I’ve made this mistake plenty of times and always regretted it.

The crab pattern happens when your code structure creates unnecessary dependencies. One side of the crab represents the importers of a central package and the other side represents the dependencies of a central package. This often happens when you group code by techincal similarity instead of what it actually does. The consequence is that if you need one part of the code, you end up pulling in everything else, which leads to a bloated, hard-to-manage dependency graph.

In Go, managing dependencies between packages is super important. Unlike other languages where the whole module might be the compilation unit, in Go, the package is the unit. That’s why circular dependencies between packages aren’t allowed. Every package you add brings along all its transitive dependencies, which makes your binary bigger, your compilation slower and your code’s purpose less clear. If you’re not careful, you can easily end up in a situation where importing one package means importing everything.

Some programmers organize code by saying, “X and Y are both Z, so let’s put them in the same package.” Z could be anything: “database access,” “third-party API client,” “utility functions,” or even “types.” For example, if X and Y are Google Cloud and AWS API clients, you might think they belong together in one package for cloud service clients. But then, if you want to use just one client, you end up importing them all. Even if someone only needs one cloud provider, they still get all the clients.

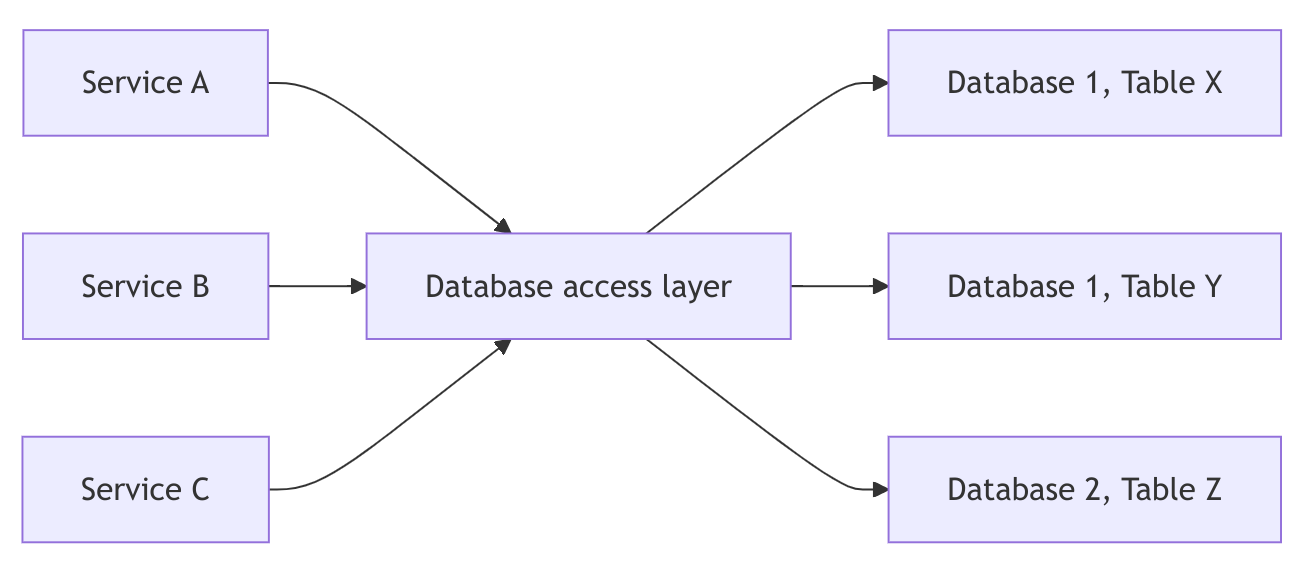

Consider a more common scenario: you’re starting a new system, maybe for a startup, and you have a single database (for now). You put all the database access code in one package, regardless of what it does. Over time, more services need to interact with the database and import that package. Eventually, you add more databases too. All the database access code stays in one package. Every service imports it, and now, if you look at the dependency graph, you can’t tell which service is interacting with which database. You’ve probably added dependencies on PostgreSQL, MySQL and MongoDB clients. You might even be compiling SQLite into all your services. This is how the crab pattern forms.

The picture below shows what my toddler calls a “crab”: a hair clip with legs that opens in half.

Now imagine your dependency graph looks like that crab. If you want to import anything, you have to import everything.

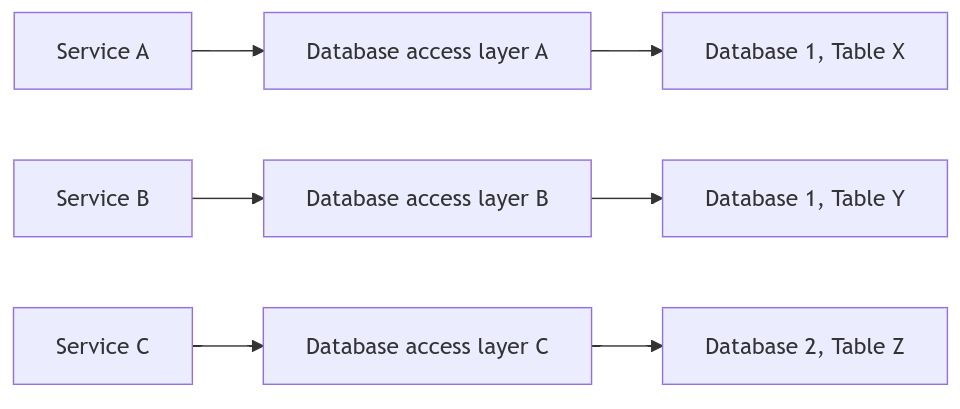

To avoid the crab pattern, create one package per feature, per table, or per product area, and organize code based on “what it does”, not “what it is.” Compare to this diagram which doesn’t contain any crabs:

By structuring your code around product functionality instead of technical similarities, you can keep your dependencies clean and your codebase manageable. Whether you’re dealing with cloud clients, databases, or utility functions, breaking things into smaller, more focused packages helps prevent everything from becoming tangled together. Think in terms of what code and external dependencies you are introducing. Keeping dependencies isolated makes it easier to maintain, extend, and understand your code and avoids turning your project into a tangled crab-like mess.