There are three other packages already that implement data loaders in go, but after using them for a while, I wasn’t happy and decided to write my own. But why?

Let’s start with “what’s a data loader?” It’s a pattern popularized by facebook in their dataloader javascript package. A data loader synchronizes multiple calls to fetch the same type of data (let’s say a user) by different keys (user IDs) and blocks the callers until “enough” of them have made a request. Then it dispatches all requests together as one batch request for multiple keys. This can turn N database calls into one. This is very useful when writing graphql code.

With that context, let’s take a look at the data loader packages that I’ve used before and where they fell short.

Dataloaden

Dataloaden is from one of the biggest contributors to gqlgen: vektah (Adam Scarr). This was an obvious choice when I was looking for a data loader because it was promoted by the gqlgen documentation and it produced simple, efficient code with a nice interface.

This is what initialization of a loader looks like:

loader := NewUserLoader(UserLoaderConfig{

Wait: 500 * time.Nanosecond,

MaxBatch: 100,

Fetch: func(keys []int) ([]User, []error) {

users := make([]User, len(keys))

errors := make([]error, len(keys))

for i, key := range keys {

if key%100 == 1 {

errors[i] = fmt.Errorf("user not found")

} else {

users[i] = User{ID: strconv.Itoa(key), Name: "user " + strconv.Itoa(key)}

}

}

return users, errors

},

})

And using it looks like:

loader.Load(key)

Very simple and elegant. There’s really nothing wrong with it except that it requires code generation. To have such a nice API, it embeds the specific types of the inputs and outputs in the generated code. It was a big inspiration for me when designing my data loader.

When generics were added to the Go language, I realized that it was possible to get rid of the code generation part, which simplifies the build process and makes it easier to use.

graph-gophers/dataloader

graph-gophers/dataloader lives under the graph-gophers org, which also publishes another Go graphql implementation called graphql-go. These days, this package is recommended by the gqlgen documentation as well as the graphql-go documentation.

This package has a longer history. It’s on version 7! It has been maintained from 2017 until now, which is a full 2 years before Dataloaden and it has gone through a surprising number of breaking changes. The up side is that it continues to get updated with new features, such as generics. At the time when I decided to create my own data loader package, graph-gophers/dataloader didn’t support generics, but now it does, and that’s a huge improvement. To be fair to them, let’s look at what usage looks like now with generics:

loader := dataloader.NewBatchedLoader(func(ctx context.Context, keys []int) []*dataloader.Result[User] {

users := make([]*dataloader.Result[User], len(keys))

for i, key := range keys {

if key%100 == 1 {

users[i] = &dataloader.Result[User]{Error: fmt.Errorf("user not found")}

} else {

users[i] = &dataloader.Result[User]{Data: User{ID: strconv.Itoa(key), Name: "user " + strconv.Itoa(key)}}

}

}

return users

},

dataloader.WithBatchCapacity[int, User](100),

dataloader.WithWait[int, User](500*time.Nanosecond),

)

And using it looks like:

loader.Load(ctx, key)()

Usage is a bit more awkward with an extra function call required to get the value, but very similar to dataloaden. The part I’m still not happy with in v7 is the initialization. There are 6 places where types have to be explicitly specified. I’m also not a fan of the result type, but that might be personal opinion. My implementation of a loader doesn’t require explicit type parameters anywhere.

yckao/go-dataloader

Well after writing my own implementation, while researching for this blog post, I noticed yckao/go-dataloader. Looks like yckao had the same idea as me around the same time. His implementation ended up looking more like graphq-gophers/dataloaders than like Dataloaden, though. I’m including the example code here for completeness.

loader := yckaodataloader.New[int, User, int](context.Background(), func(_ context.Context, keys []int) []yckaodataloader.Result[User] {

results := make([]yckaodataloader.Result[User], len(keys))

for i, key := range keys {

if key%100 == 1 {

results[i] = yckaodataloader.Result[User]{Error: fmt.Errorf("user not found")}

} else {

results[i] = yckaodataloader.Result[User]{Value: User{ID: strconv.Itoa(key), Name: "user " + strconv.Itoa(key)}}

}

}

return results

},

yckaodataloader.WithMaxBatchSize[int, User, int](100),

yckaodataloader.WithBatchScheduleFn[int, User, int](yckaodataloader.NewTimeWindowScheduler(500*time.Nanosecond)),

)

And using it looks like:

loader.Load(ctx, key).Get(ctx)

The new package: dataloadgen

With all this context, let’s look at example usage of dataloadgen. It’s very similar to Dataloaden. The idea was basically “dataloaden with generics”.

loader := dataloadgen.NewLoader(func(_ context.Context, keys []int) ([]User, []error) {

users := make([]User, len(keys))

errors := make([]error, len(keys))

for i, key := range keys {

if key%100 == 1 {

errors[i] = fmt.Errorf("user not found")

} else {

users[i] = User{ID: strconv.Itoa(key), Name: "user " + strconv.Itoa(key)}

}

}

return users, errors

},

dataloadgen.WithBatchCapacity(100),

dataloadgen.WithWait(500*time.Nanosecond),

)

And using it looks like:

loader.Load(ctx, key)

The most important thing to note is that there are no explicit types anywhere. It also doesn’t use a Result type. It uses an options pattern to make it more extensible and that came in handy when adding tracing support. It has open telemetry tracing built in that’s fairly easy to turn on. And finally, it performs better.

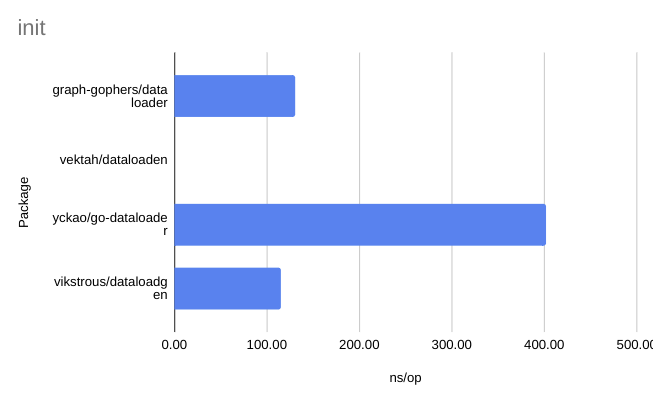

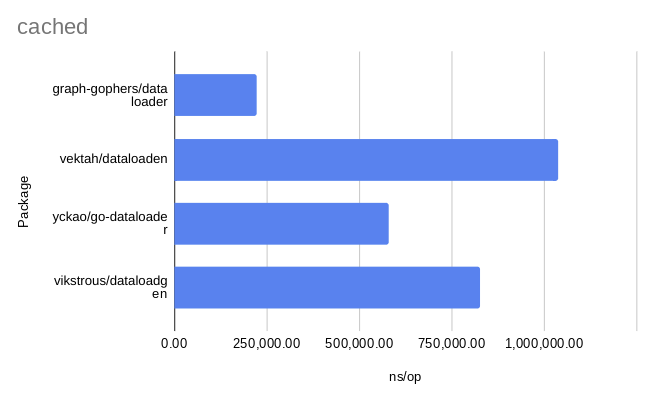

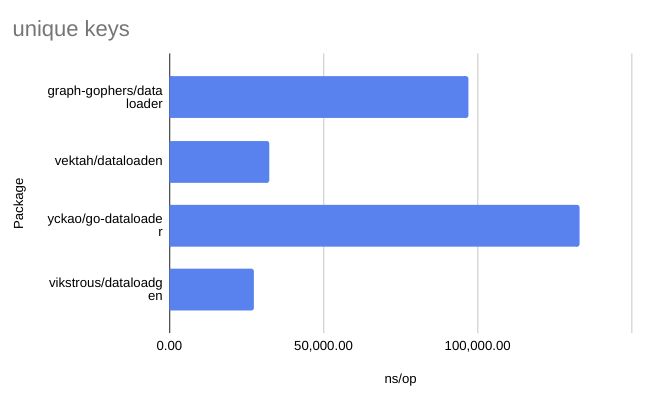

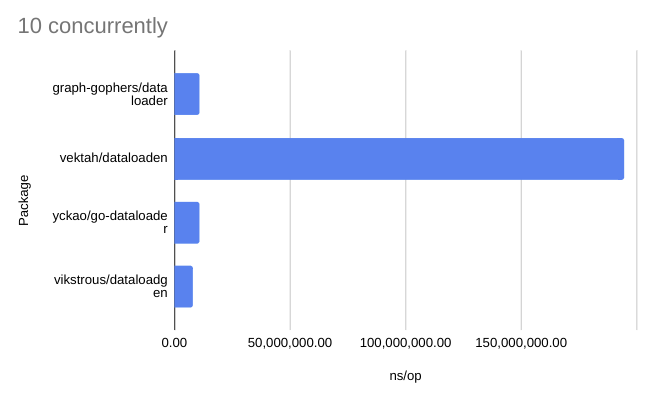

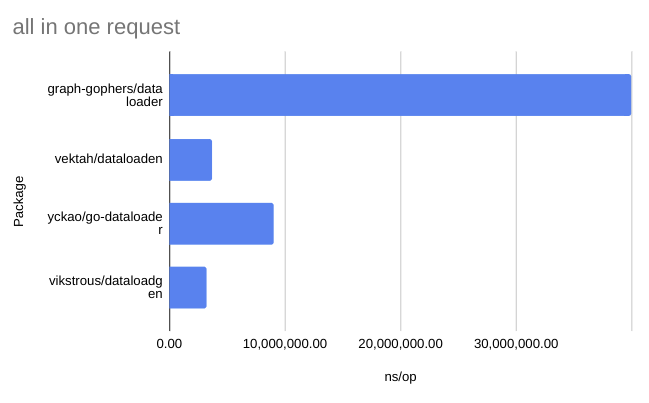

I spent a considerable amount of time optimizing the code and writing benchmarks for all 4 packages to prove to myself that it’s not worse in any way. I would love to hear if others also find it useful. Try it out!

Check out the readme for the results of the benchmarks. They are also copied below: